Argyle's communication cycle looks simple on paper. That’s the reason students mess it up. Most can list the stages from memory, but they still freeze when they are asked to explain how the communication process works in real life. The examiner also sees the same problem every time: the vague answers, no examples, and weak applications. That’s how students lose marks. Well, this guide is going to fix that gap; you’ll get a clear explanation of the Michael Argyle communication model with practical examples. Not just that, you’ll also get an assignment-ready understanding that actually fits your marking criteria. No theory overload, just clarity.

What Is Argyle’s Communication Cycle?

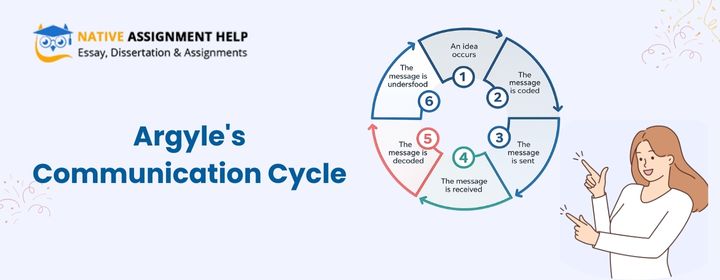

The Argyle Communication Cycle was developed by British psychologist Michael Argyle in the 1970s. He studied how people interact in everyday life, especially how messages pass back and forth in interpersonal communication. Then Argyle noticed that communication isn’t just about sending words. It's actually a loop where the sender, receiver, and feedback make each and every thing matter. His model breaks this down into stages, showing that understanding depends on both giving and receiving signals.

At its core, the cycle explains two-way communication: you send a message, the other person interprets it, reacts, and you adjust based on their response. This is what makes the process continuous and dynamic, not just one-sided. In today's world, it’s still relevant in classrooms, workplaces, and even online chats. For exams, this model is assignment-ready, helping students apply theory with examples instead of just memorising stages.

The Six Stages of Argyle’s Communication Cycle

Argyle’s model only works when each stage connects clearly to the next. If the one stage is weak or missing, then communication fails and students lose marks in exams and the assignments.

1. Idea Occurs

This is from where the communication begins. An idea forms in the sender’s mind based on their thoughts, emotions, past experience and the situation they are in. At this stage a person's idea may be just a vague thought, but from here only everything shapes. Also, stress and confidence weaken the idea before it is even shared, which is why messages often start unclear.

- Student example: A student thinks about asking a lecturer to clarify an assignment deadline but feels nervous about sounding unprepared.

- What usually goes wrong: students rush in this stage, which makes them describe the sentence unclearly. Forgetting that weak or unclear ideas lead to weak communication.

2. Message Coded (Encoding)

While coming to the next stage, the sender turns the ideas into words, tone, and actions. This also includes language choices, sentence structure, facial expressions, and body language. The message follows the original concept when the encoding is clear. Using wrong words or an unclear tone means poor encoding, which often leads to misunderstanding before the message is even delivered.

- Student example: A student chooses formal words and a polite tone when emailing a lecturer about an assignment issue.

- What usually goes wrong: Students use vague language or ignore non-verbal cues, which changes the meaning of the message.

3. Message Sent

At this stage, the sender chooses a method of communication, such as spoken, written, or digital. The channel affects how clearly the message is understood. In this situation, digital communication is weaker because tone, emotion, and body language are often absent, which increases the chance of confusion.

- Student example: A student sends an assignment-related question through email instead of asking face-to-face.

- What usually goes wrong: Students ignore how the channel changes meaning and assume the message will be understood the same way everywhere.

4. Message Received

This stage begins when the receiver gets the message. Here understanding depends on attention, focus, and the surrounding environment. Whereas noise, stress, or multitasking reduces the efficiency of the message that is actually received. Even a clear message can fail if the receiver is distracted.

- Student example: The professor reads students' emails while being busy, which results in missing important details.

- What usually goes wrong: Students don’t recognise distraction acts as hidden barriers, and they assume receiving a message always means understanding.

5. Message Decoding

When the message is interpreted by the receiver and given a meaning, that’s called decoding. The process is influenced by cultural background, emotions, and personal experience. As we know, a single message can be understood in different ways according to the person.

- Student example: A student reads brief feedback from a lecturer and assumes it is negative due to stress.

- What usually goes wrong: Students think decoding is automatic, and they ignore how personal filters change the meaning of each message.

6. Feedback

The answer or response given by the receiver shows whether the message was clear and makes the communication process cyclical. Without any feedback, the sender cannot know if the message was understood correctly.

- Student example: A reply from the lecturer confirms the assignment deadline and clears the confusion.

- What usually goes wrong: Not answering back can break the cycles and lead to incomplete communication.

How Information Flows in Argyle’s Communication Cycle

Argyle’s communication cycle should not be understood as a straight-line process. Instead, it works as a continuous loop in which communication moves forward but constantly returns through the feedback. Each stage of the cycle affects the next, meaning that a weakness at any point can affect the overall outcome of the interaction. That is the reason communication succeeds or fails based on how smoothly information flows between the sender and receiver. Strong feedback keeps the process active and balanced.

The flow begins when an idea forms in the sender’s mind. Then, these ideas are encoded in words, tones, or gestures and transmitted through chosen channels, such as speech or digital media. The receiver obtains the message and decodes its meaning based on context, experience and emotional states. Feedback then confirms whether the message has been understood or the confusion still remains. This feedback allows the sender to adjust or solidify the message, causing the cycle to continue.

In examinations, Argyle’s model should be explained as a two-way communication process rather than a linear exchange. Feedback is the defining feature examiners expect, as it demonstrates whether a message has been understood or misunderstood. This cyclical flow explains why communication can fail in real-life situations even when a message appears clear at the point of delivery.

Real-Life Case Studies of Argyle’s Communication Cycle

This section demonstrated the practical application of the theoretical knowledge. Here, each case shows how the six stages operate in real-life situations. Additionally, the section elucidates the significance of feedback in communication as a crucial component of an effective communication process.

Student–Lecturer Communication Case Study

A perfect example of Argyle’s communication cycle can be seen when students seek clarification from a lecturer. After looking at the assignment brief, students often become unsure about the submission and opt to seek clarification. However, the ideas formed from confusion and academic pressure lack clarity and urgency when the student encodes them in the email.

The message is sent through written communication, which removes tone and non-verbal cues. When the professor receives and decodes the email, they interpret it as a general enquiry rather than a serious concern. As a result, the lecturer gives short and generic feedback that doesn’t address the student’s uncertainty, leaving the communications cycle incomplete.

This situation can be efficiently analysed using a reflective model like the Driscoll model of reflection.

- What? The student’s unclear query expression and choice of written communication caused misunderstandings during decoding.

- So what? Weak feedback failed to confirm understanding, which increased confusion and also delayed the communication.

- Now what? By re-encoding the message with specific details and requesting confirmation, the student received clear feedback that resolved the issue.

This final feedback closes the communication loop and restores two-way communication. This case highlights how encoding quality, channel choice, and reflective feedback together influence the effectiveness of Argyle’s Communication Cycle in academic settings.

Doctor–Patient Interaction Case Study

A doctor-patient interaction demonstrates how decoding differences can affect communication within Argyle’s communication cycle. A patient visits a doctor to explain persistent headaches and fatigue. The idea forms when the patient steps up to describe the symptoms, and during expressing, the patient uses everyday language rather than medical terminology.

Here, professional training and clinical assumptions heavily influence the doctor’s decoding when they receive the message. They interpret the symptoms through a medical perspective and initially consider stress-related causes. Although the message itself is clear, the meaning shifts because the sender and receiver decode it using different knowledge frameworks.

The communication gap appears when the patient shows confusion and worry. This feedback shows a mismatch between the doctor’s interpretation and the patient’s experience. Consequently, the doctor asks follow-up questions to help the patient to clearly express the symptoms in detail. When the patient provides additional information, doctors adjust the explanation accordingly and fill the understanding gaps.

This case shows that communication can fail even when the messages are clearly expressed. The breakdown occurs during the decoding process. whereas feedback plays a corrective role after mismatched interpretations are revealed, and that allows the communication cycle to continue accurately. It also strengthens the importance of two-way communication in Argyle’s model.

Manager–Employee Workplace Communication Case Study

A manager assigns a new task to an employee during a brief discussion at work. Here the idea is to complete the task quickly, but during encoding, the manager gives short instructions. The manager assumes that the employee is already aware of the priorities and the deadline. However, the manager fails to explicitly state the crucial details.

The message is sent through verbal communication, relying more on authority rather than clarity. Now the employee receives the message but decodes it on the basis of personal assumption and understanding, focusing on the task itself rather than the urgency. As a result, the work is completed, but it could not meet the manager’s expectation with late delivery.

Feedback only occurs after the task is reviewed. At this point, the manager points out the errors and explains what he expected from the task. The employee asks for clarification and the manager re-encodes the message now with clear priorities and deadlines. Despite correcting the misunderstanding, the time and resources have already been wasted.

In this case, we understand how authority can weaken encoding, how assumptions distort decoding, and why delayed feedback does not prevent failure. Instead, feedback that arrives late only fixes things after damage has already occurred. This reinforces the importance of timely two-way communication in Argyle’s Communication Cycle.

Communication Barriers in Argyle’s Communication Cycle

When one or more steps in Argyle's Communication Cycle aren't working properly, communication barriers begin to interfere. These obstacles are not present at random; rather, they impede clear comprehension and weaken particular parts of the cycle.

- Stress, anxiety, and low self-esteem are examples of emotional barriers that can get in the way of forming and decoding ideas. It also triggers how a message is interpreted, leading to unclear communication.

- Encoding and decoding are influenced by cultural barriers. The intended meaning of a message can be altered by variations in values, gestures, or communication styles.

- Language barriers weaken encoding. Limited vocabulary or complex terminology makes messages difficult to express or understand accurately.

- Technological barriers affect the message-sent stage. Digital communication often removes tone and non-verbal cues, increasing the risk of misunderstanding.

- The message-received stage is disrupted by environmental noise. Attention and clarity are diminished by physical interruptions or distractions.

In Argyle’s model, feedback plays a corrective role. On-time feedback solves misunderstandings while allowing messages to be re-encoded and keeping the communication cycle going.

Advantages and Limitations of Argyle’s Communication Cycle

This balanced evaluation highlights the advantages and disadvantages of Argyle’s model while clearly addressing the limitations of Argyle’s communication cycle, which is exactly what examiners and search engines expect.

|

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Clear two-way flow: The model explains communication as an interactive process rather than a one-way transmission. |

Weak in mass communication: It is designed for interpersonal interaction and does not fully apply to large-scale or one-to-many communication. |

|

Emphasises feedback: Feedback allows misunderstandings to be identified and corrected, making communication continuous and effective. |

Oversimplifies complex contexts: Real-life communication can involve multiple participants and overlapping messages, which the model does not fully capture. |

|

Useful for interpersonal settings: It works well in classrooms, workplaces, and everyday conversations. |

Less effective in digital-only interaction: Online communication often lacks non-verbal cues, reducing the model’s practical accuracy. |

Comparison With Other Communication Models

Argyle’s Communication Cycle is mainly used for interpersonal communication, where understanding depends on feedback and response. It explains everyday interactions clearly, such as conversations between students and teachers or managers and employees. Because it focuses on two-way communication, it is easy to apply in assignments and real-life examples.

In comparison, the Shannon–Weaver Model is more suitable for mass and technical communication, where messages are sent one way and noise affects delivery. Berlo’s Model helps analyse message structure but gives less importance to interaction. Argyle is closer to the transactional model of communication, as both highlight continuous exchange, making Argyle more practical for human communication.

How to Use Argyle’s Communication Cycle in Assignments & Exams

In Argyle’s communication cycle assignment, examiners expect more than listing stages. You must show understanding and application. The safest structure is:

- Brief definition of Argyle’s Communication Cycle

- Explain the stages with clear logic

- Apply one real-life example (academic or workplace)

- Add brief criticism (limits or barriers)

Use examples where feedback clearly changes the outcome. This shows you understand two-way communication rather than memorising theory. If students struggle with structuring answers or applying theory correctly, communication assignment help or guidance for communication theory assignments can improve clarity and marks.

Sample exam-style paragraph:

Argyle’s Communication Cycle explains communication as a continuous two-way process involving feedback. For example, in student–lecturer communication, unclear encoding can lead to misunderstanding until feedback corrects the message. However, the model is less effective in mass communication, showing its limitation in complex contexts.

Common Mistakes Students Make

- Listing the six stages without explaining how they connect in real communication

- Memorising definitions instead of applying Argyle’s model to real-life examples

- Ignoring feedback, even though it is the core feature of the communication cycle

- Failing to include any criticism or limitations in exam answer

- Treating Argyle’s model as a straight line instead of a continuous loop

- Confusing Argyle’s Communication Cycle with linear models like Shannon–Weaver

- Writing generic answers that lack clarity, structure, or evaluation

Students who identify these mistakes early often benefit from structured academic writing services, especially when working on theory-based assignments and exams.

Conclusion: Why Argyle’s Communication Cycle Still Matters

Argyle’s communication cycle explains how communication works in real situations. This makes it more relevant and free from just theory. The method highly focuses on feedback and interaction, which makes it useful for understanding academic and workplace communication easily. For students, the real value of this model lies in its application rather than in memorisation. Furthermore, just listing the stages rarely earns marks; one has to use clear examples, identify barriers, and add brief evaluations to demonstrate genuine understanding. If a learner applies it correctly, Argyle's model helps in explaining why communication succeeds or fails. Students who struggle to structure or apply such models often benefit from assignment writing help to improve clarity and academic accuracy.

I hope Argyle’s communication cycle will be very helpful in providing ideas to strengthen your conversations. If you’re struggling to use it in your assignments, then you can approach Native Assignment Help services. We provide structured assistance to students to complete their projects and enjoy a proper learning experience.